In the early 1990s, when I was a student, I visited an art exhibition with photographs by Sugimoto Hiroshi. It was from a series called Seascapes. The photographs were all in black and white. They had been taken around the world with a view camera, but all showed the same thing: the sea and the sky, with the line of the horizon cutting the picture in two halves. Sometimes it was almost night, sometimes the horizon disappeared in fog, sometimes it was as thin and clear-cut as a pencil line on a white paper.

The museum sold a limited edition of these pictures, in a metal box. I could buy it, almost. It was certainly expensive for a student, unreasonable even, but still possible. I hesitated. Left. Went back the next day, left again. It went on for a week or two, then reason prevailed and I didn’t buy the work. I’ve regretted it ever since, and perhaps because of this, I never bought a work of art, even when, later in life, I could afford it.

But now I just bought a Future Library Certificate, 2014 - 2114 by Katie Paterson. It is both a work of art, and a public project.

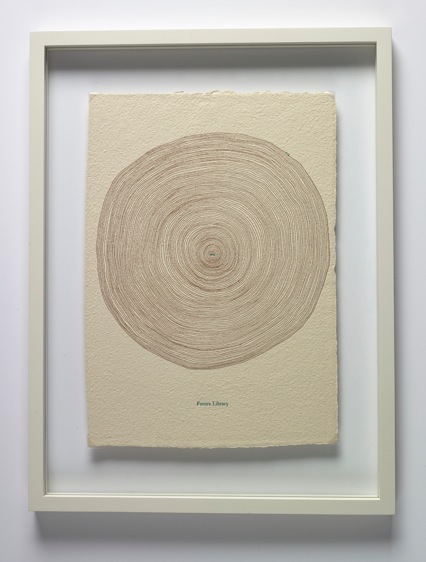

The work is simple enough: it represents tree rings, with 2014 inscribed in the centre and 2114 at the edge. But at the back a text explains that this is really a voucher for a series of books to be published in 2114.

The public project is much more complex.

In a forest north of Oslo, they have cut some trees, to be used to build a new room in the public Deichmanske bibliotek in Oslo. New trees have been planted in their stead. In 2114, those trees will in turn be cut down and used to produce the books promised by the certificate.

Meanwhile a trust managing the project selects a writer every year, who contributes a secret text to the project: nobody but the author will be able to read the text until the project is completed in 2114.

The texts are kept, unread, in that room at the Deichmanske bibliotek.

Three authors have given texts so far :

- Margaret Atwood (2014)

- David Mitchell (2015)

- Sjón (2016)

This project is both plain (trees for the future) and subtle in many different ways that touch me personally.

I sometimes write. And if I think as a writer, I realize how difficult it must be to contribute to this project. Should I make a short poem? Or should I contribute a large text? A hundred years is a long time to wait for a book, people will want to have a decent text for their money, surely? What happens if I’m paralyzed by all this and can’t contribute anything, not one word, “nada”? Nobody would know, would they? And what to write? Obviously, I can’t write that the character wrote a “blog post” or “pulled out her cell phone”. Or can I? And the language itself, it moves so quickly : can I write that “Elle s’enivra de vin doux”? Will that not sound terribly quaint in 2114?

Will there even be a reader? I can’t get any feedback on my work. Writers complain that their text escapes them when it’s published. Mine would be finished, yes, but not published. Posthumous publishing is generally supposed to be by accident, not by design. Am I producing a dead man’s text?

I can’t talk about the text either. It’s a secret: I created a taboo for myself. And that notion is so tightly linked to shame: should one be ashamed of writing a text for the Future Library project?

On the other hand: a secret! I’ll be dead, I couldn’t care less what people will think, right? I can write things I wouldn’t normally dream of putting to paper. Better than the shrink. Sure everyone needs constraints to write, but I can certainly discard the limit on “not hurting people” or “not making a fool of myself” - even though writing is profoundly about shame, always, isn’t it?

This is such a great plot.

But writing is not how I earn a living: I’m a librarian. If I think about the project from the Deichmanske’s point of view, I know where this project stands. I’m an institution, people have faith in me to preserve and transmit a certain idea of our community. Politicians, entrepreneurs, citizens come and go. As a community, we persevere. We mutate, neighbourhoods decay and rise, activities move around, our fortunes ebb and flow, but we persevere. That little room where the manuscripts are kept is a space and time capsule, it is a vehicle we use to both protect ourselves from the elements, and to travel to where we want to be, in a future where literature, nature and community are intertwined and continue to shape a reality we can still recognize as ours. Libraries are living organism where this bizarre plant, our culture, can continue to grow: not a seed vault, a greenhouse.

Then, I’m a city guy. I grew up in the suburbs of a mid-sized French city, I now live in Paris. You remember Coruscant? It’s the capital planet of Star Wars, a planet wide city approached in awe by incoming spaceships. It is beautiful and frightening, as every city should be. There’s no nature in Coruscant, except for the lingering clouds in the atmosphere, and maybe the succession of day and night. And by the way, Coruscant is at once the posh, clean twin sister of Blade Runner’s Los Angeles, and a copy of Asimov’s Tranton, wich, in his Foundation cycle, is described as the cradle of humanity. And to me, indeed, cities feel like the cradle, if not of humanity, certainly of civilization.

But for 3 years, in 2014-2017, I’ve lived in the Caribbean, where the sun sets very decidedly at around 6 p.m. year round. The islands are small. You can climb a volcano there and, from the top, see both the Atlantic ocean to the East, and the Caribbean sea to the West. You can walk back to the beach in an hour or two, put on palms and continue your way under the surface of the water, where you see that indeed, the slopes of the volcano continue, with crevices and plateaus full of inquisitive barracudas and urchins moving their spines in the coral reefs.

When I get back home, it’s so hot I close the blinds, I drink an iced tea and watch Star Wars with my daughter. We’re tired from the walk and the swim, we doze off and dream of fishes and beams of light in the water.

I want my daughter to continue having those mixed dreams of cities and nature. Of a planet that, because it’s still a separate entity from us, can be the object of meaningful interactions. I want to see people walking to the forest outside Oslo, for many years to come, and talk.

Finally, I’ve been to Norway three times, always for short, work-related trips. But the country’s left a mark with me. It is among the most democratic, open societies in the world. It is not a pristine paradise, devoid of contacts with reality, as both Breivik and the land border with Russia will remind anyone, but to me it certainly represents one of the pinnacles of what a modern European society can be.

For all these reasons, I’ve bought a Future Library Certificate. Someone will someday use this certificate n°366/1000 and gather the texts written over a century: I’ll have a link to that future person. In the meantime I intend, when I can, to travel to Oslo, see the room in the library, see the trees in Nordmarka, maybe talk to the community of people who are participating in this project - who, like me, have a certificate, or who went to one of the yearly handing ceremony, or who cut the trees and built the room at the library.

The Future Library project is at once literary and artistic, civic and deeply personal; it projects us into the future and defies time. I feel there’s not much more you can ask of art.